This is a story of some relatively big code refactoring and my experience of using Claude code for it.

At Uber, we have a Go service for generating financial statements for users (let’s call it service X). Over time, this service grew into a pretty hefty monolith service which includes data fetching, massaging and presentation logic. We had to build a new service (service Y) for a different type of reporting that should re-use the data fetching part of the X service. Unfortunately, this part had typical features of legacy code - written long time ago, not well maintained but at the same time was updated with some frequency which made the quality rather worse than better with every diff.

Service framework

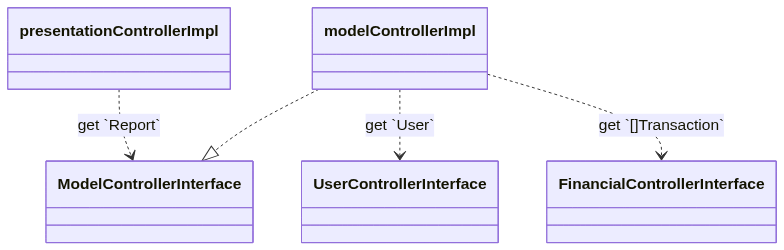

Before I go further, I should mention a few words about how a typical Go service at Uber is structured. Usually services contain most of their business logic in Controllers - singletons exposed as interfaces. Each controller represents a micro domain and should abstract their logic from other controllers. Controllers can call other controllers. Here’s a UML like diagram that depicts an artificial example:

When you write a unit test for modelControllerImpl, you can only mock other interface dependencies. If modelControllerImpl calls a method on a struct (not interface) or a static function - it can’t be mocked.

func (c *modelControllerImpl) GetReport(...) (Report, error) {

user := c.UserControllerInterface.GetUser(...) // interface invocation - can be mocked ✅

transactions := c.FinancialControllerInterface.GetTransactions(...) // interface invocation - can be mocked ✅

dateOfBirth := user.GetDateOfBirth() // invocation of a method of a struct - cannot be mocked ❌

dateOfBirthString := formatter.FormatDate(dateOfBirth) // invocation of a static function from package `formatter` - cannot be mocked ❌

...

}

Challenges

Going back to the main topic of this post, in order to re-use the wanted logic, I needed to move it into a shared library. The problem was that this logic had not been isolated as its own controller or even method of a controller. The logic was spread across multiple places of one big data fetching controller. The size of the production code of the controller alone was ~4700 lines. The difficulty was not about finding the right pieces to move and move them but fixing the tests after that because the moved logic would start to live under a new interface in the new library. Imagine you have 3 functions that call each other: a() -> b() -> c(). The unit tests of function a() are written under an assumption that function c() can be executed as is. If due do refactoring function c() got moved into a library, the production code will change so that this function is requested from the new dependency interface:

// before:

func (c *controller) a() {return c.b()}

func (c *controller) b() {return c.c()}

func (c *controller) c() {return "foo"}

// after c() was moved to the controller newDep as C():

func (c *controller) a() {return c.b()}

func (c *controller) b() {return c.newDep.C()}

Such refactoring is probably going to break your test because now you need to define mocks for the call to function C() properly for every test. Alternatively, you can use the real implementation for newDep instead of mock however this is not ideal because it violates interface isolation. But even that might be hard to do if your original function c() depended on another interface in your original implementation.

The refactoring was big enough to make me split this work into multiple diffs. And at every diff I had to go through the painful experience of updating such tests. In the example above, in the first diff, I move function c() behind an interface and have to update the tests. In the second diff, I move function b() and the mocks in the unit tests of function a() have to updated once again.

The original controller was enormous and at the end of the refactoring, the moved part resulted in 18 controllers. The size of the original controller decreased from 4700 to 2900 lines of code. These numbers can give you an idea of how tedious the process of updating the tests was.

How I used claude code

I use claude code quite often and this task was not an exception. Here’s what I tried doing with it.

Generating unit tests

I still don’t fully trust claude when I ask it to do something big. Luckily, most people have tests and they create guardrails that allow us to be bold with outsourcing work to AI. In this refactoring, old tests were not creating such guardrails. If we look at the example above once more, it was quite common when function a() had tests but functions b() and c() didn’t. After I moved b() and c() under the new controllers, I couldn’t “move” their tests since those functions were covered by the tests of function a(). One could argue that I could rely on E2E tests in such case but E2E tests for this service were way not enough to provide good coverage for the refactored functions.

That led me to the idea that for refactoring I can trust either tests (was not possible in this instance) or the implementation. The implementation of the refactored functions were not changing. The only aspect I should be careful about is how I call those functions after I moved them behind controllers. So, for this reason, I decided to move the implementation myself manually to guarantee it doesn’t change and rely on claude code for unit tests generations. I wouldn’t need to be careful with creating test cases due to high confidence in the implementation accuracy. I could simply generate 100% line coverage unit tests and don’t think much about test cases from a product point of view.

As I said, I was moving the old logic piece by piece by putting them in new controllers. In the scope of a single diff, I was working on multiple controllers. And while I was moving yet another controller manually, I made my claude generate unit tests for those that I’ve just moved. I was generating unit tests in 2 stages. Stage 1: scaffold the test function and create one happy path scenario. This was necessary because I was not happy with how claude usually generates unit tests. Sometimes it missed expected arguments on mocked dependencies, sometimes the body of the test was more complicated than it should. Having rules in claude.md was not enough. Therefore I wanted first to make sure I’m satisfied with how the first test look like. Stage 2: generate unit tests to ensure 100% coverage. Having one good example of a test scenario increased the quality of the rest of the tests significantly.

Most people prefer the “commit often” principle when they work with AI tools and I do the same. Eventually, I started using a sort of a template for my commits to help me track my progress within a single diff. It looked something like this:

controller name | logic moved manually | 1st test generated and verified | all tests generated and verified

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

controllerA | DONE | DONE | DONE

controllerB | DONE | DONE | WIP

controllerC | WIP | WIP | WIP

It was possible to parallelize the work of the agents. If there were more than one controllers ready for the test generation phases (that happened all the time), I’d just run one claude code agent per controller. They didn’t need to share anything between each other and therefore it worked pretty good and fast.

Tracking progress

I was a bit nervous about this refactoring because I find estimating refactoring very hard. I knew that this work is going to take several weeks and multiple diffs and therefore I wanted to find a way to track the progress. I decided to measure how many code entities I still need to move. At the beginning of this work, I only knew the final function that needs to be moved and shared. At Uber, we use bazel and it could be possible to generate a dependency graph based on bazel rules. However, in this refactoring, almost all needed logic lived in one controller which means a single bazel rule which made this approach not helpful.

Instead, I asked claude code to generate a mermaid graph of all function dependencies starting from the final goal function. The generated graph depicted functions, structs and interfaces as nodes and calls and usages as edges. I asked it not to dive inside dependencies if they were exposed through other existing interface because moving them was not a problem. I also used some color coding to make the graph reading easier.

Eventually, I had a reusable prompt that could generate me a mermaid chart and statistics for node and edge counts. It worked pretty well for me and gave me some confidence as I saw my progress.

Below are pictures of how the charts looked like at the beginning and at the end of this effort:

Chart before refactoring:

Nodes: 85

Edges: 146

Chart after refactoring:

Total nodes: 28

Total edges: 81

Review

Another interesting (but I suppose quite common) application of claude was the review of the code. I was not interested in reviewing the moved code. This is legacy code, it has issues and despite that I was not intended to fix them since my goal was to make the existing logic shareable as is. What I asked it to do is to find what could have changed as a result of the refactoring from the business logic perspective. At every diff, I pointed claude to the diff where the refactoring changes were made to narrow down its search. And it indeed found one case where I by mistake changed the parameters with which a newly added controller was called. It’s possible that it could’ve been detected during my own code or peer review but it was not guaranteed.

What didn’t go well

Claude still performs poorly on big files. This was especially common for updating the unit tests of the old controller (see the “Challenges” section). Quite often it would just fix 3 out of 100 tests, spend dozen of minutes on this and stop. Even if I was very specific about how those tests had to be fixed.

Similar story with moving highly used constants to a new package. It managed to change some occurrences but far from all. In the end I did it in combination with bazel runs + claude, regex and some manual work.

Conclusion

I think my work on this task was definitely improved by claude. It gave me a significant performance boost. Mainly because generating new unit tests for all those functions would be slow, tedious and repetitive (i.e. mistake prone). And “tedious and repetitive” is a category where gen ai products today shine and therefore I think this task was a very good fit for it.